Αναδημοσίευση από Βήμα 18/12/11

Μαρξιστής κατά αθεϊσµού

Ο βρετανός λογοτεχνικός κριτικός και θεωρητικός του πολιτισµού Τέρι Ιγκλετον υπερασπίζεται τη χριστιανική πίστη απέναντι στους νεοαθεϊστές

«Σε µια εποχή που η πολιτική Αριστερά βρίσκεται σε δεινή ανάγκη για καλές ιδέες, ο λόγος της θρησκείας θα µπορούσε να προσφέρει πολύτιµες εναισθητικές γνώσεις για την ανθρώπινη χειραφέτηση» υποστηρίζει ο κριτικός και θεωρητικός του πολιτισµού Τέρι Ιγκλετον. Βρετανός της εργατικής τάξης ο οποίος ανατράφηκε ως κοινός ρωµαιοκαθολικός ιρλανδικής καταγωγής, µε το βιβλίο του Λογική, πίστη και επανάσταση εµφανίζεται ως αυτόκλητος υπερασπιστής της θρησκευτικής πίστης, εν προκειµένω της χριστιανικής, απέναντι στη νέα σχολή ενός µανικού αθεϊσµού, που εντοπίζεται στα πρόσωπα και στα κείµενα του βιολόγου Ρίτσαρντ Ντόκινς και του δηµοσιογράφου Κρίστοφερ Χίτσενς – του διδύµου «Ντίτσκινς», όπως τους αποκαλεί χάριν συντοµίας.

Στη µετανεωτερική εποχή η θρησκεία βρίσκεται παντού σε άνοδο, το ενδιαφέρον όµως είναι ότι ξαναγίνεται δηµόσια και συλλογική και τείνει συχνά να πάρει πολιτική µορφή – φαίνεται πως είναι πάλι έτοιµη να ξεσηκώσει και να σκοτώσει. Κοσµικοί διανοούµενοι τύπου Ντίτσκινς ανασκουµπώθηκαν για να πολεµήσουν αυτό το σκοτεινό, ανορθολογικό πρόσωπο της θρησκείας.

Ο Ιγκλετον δεν αρνείται ότι η θρησκεία έχει υπάρξει µια «βρωµερή ιστορία µισαλλοδοξίας, δεισιδαιµονίας, ευσεβών πόθων και καταπιεστικής ιδεολογίας» και ότι ο χριστιανισµός έχει προδώσει τις επαναστατικές του καταβολές περνώντας από το πλευρό των απόκληρων στο πλευρό ψευδόµενων πολιτικών, διεφθαρµένων τραπεζιτών και φανατικών νεοσυντηρητικών. Εκείνο όµως που πυροδοτεί την πολεµική τού αταλάντευτου µαρξιστή Ιγκλετον είναι το γεγονός ότι οι πολέµιοι του θρησκευτικού φονταµενταλισµού δεν ασκούν καµία κριτική στον παγκόσµιο καπιταλισµό, ο οποίος δηµιουργεί τα αισθήµατα άγχους και ταπείνωσης που τρέφουν τον φονταµενταλισµό. Πολύ βολικά, οι κληρονόµοι του φιλελευθερισµού και του ∆ιαφωτισµού ξεχνούν ότι έχουν επίσης προδώσει τις θεωρητικές τους διακηρύξεις, όπως αποδεικνύουν η βίαιη υπεξαίρεση της ελευθερίας και της δηµοκρατίας στο εξωτερικό, ο ρατσισµός, η αποικιοκρατία, οι ιµπεριαλιστικοί πόλεµοι, η Χιροσίµα, το απαρτχάιντ, η υποταγή στους σκοπούς του εµπορικού κέρδους.

Επιστρατεύοντας στο οπλοστάσιό του θεολόγους, πολιτικούς επιστήµονες, ιστορικούς, φιλοσόφους και λογοτέχνες, από τον Θωµά τον Ακινάτη ως τον Μαρξ, τον Φρόιντ, τον Λακάν, τον Σλάβοϊ Ζίζεκ, τον Τσαρλς Τέιλορ, τον Αλέν Μπαντιού, τον Μίλτον και τον Τόµας Μαν, ο Ιγκλετον τονίζει ότι οι σχέσεις µεταξύ γνώσης και πίστης είναι περίπλοκες, αλλά πρόκειται για δύο διαφορετικά πράγµατα τα οποία δεν παραµερίζουν το ένα το άλλο. Η φανατική θρησκευτική πίστη της µετανεωτερικής εποχής άνθησε ακριβώς επειδή η λογική έγινε υπερβολικά κυριαρχική και εργαλειακή, µε αποτέλεσµα να µην µπορεί να ευδοκιµήσει στο έδαφός της ένα έλλογο είδος πίστης. Αυτός όµως δεν είναι λόγος για να αρνηθούµε την πίστη εξ ολοκλήρου.

Το όραµα του φιλελεύθερου ανθρωπισµού για ελεύθερη και ευτυχή ανάπτυξη της ανθρωπότητας είναι εφικτό, καταλήγει ο Ιγκλετον, µόνο µέσω της αντιµετώπισης του χειρότερου εαυτού µας µέσα από µια διαδικασία αυτοαλλοτρίωσης και ριζικής αναδηµιουργίας, µια διαδικασία, όπως την αποκαλεί χαρακτηριστικά, «τραγικού ανθρωπισµού». Η θρησκεία, εκτιµά ο βρετανός θεωρητικός, θέτει ερωτήµατα για ζωτικά ζητήµατα, για τον θάνατο, τον πόνο, την αγάπη, την αυτοαλλοτρίωση, για τα οποία η σηµερινή κοινωνία και η πολιτική σιωπούν και ο Ιγκλετον αποφασίζει εδώ να κηρύξει το τέλος σε αυτή την «πολιτικά

Πέμπτη 29 Δεκεμβρίου 2011

Συνέντευξη Terry Eagleton για το "Λογική,Πίστη,Επανάσταση"

Αρχική Δημοσίευση :voidmanufacturing.wordpress.com

Literary critic Terry Eagleton discusses his new book, Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate, which argues that “new atheists” like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens “buy their rejection of religion on the cheap.” He believes that, in these controversies, politics has been an unacknowledged elephant in the room.

Nathan Schneider: Rather than focusing on “believers” or “atheists,” which are typically the categories that we hear about in the new atheist debates, you write about “a version of the Christian gospel relevant to radicals and humanists.” Who are these people? Why do you choose to address them?

Terry Eagleton: I wanted to move the arguments beyond the usual, rather narrow circuits in order to bring out the political implications of these arguments about God, which hasn’t been done enough. We need to put these arguments in a much wider context. To that extent, in my view, radicals and humanists certainly should be in on the arguments, regardless of what they think about God. The arguments aren’t just about God or just about religion.

NS: Are you urging people to go to church, or to read the Bible, or simply to acknowledge the historical connections between, say, Marxism and Christianity?

TE: I’m certainly not urging them to go to church. I’m urging them, I suppose, to read the Bible because it’s very relevant to radical political concerns. In many ways, I agree with someone like Christopher Hitchens that most religion is fairly hideous and purely ideological. But I think that Hitchens and Richard Dawkins are gravely one-sided about the issue. There are other potentials in the gospel and in the Christian tradition which are, or should be, of great interest to radicals, and radicals haven’t sufficiently recognized that. I’m not trying to convert anybody, but I am trying to show them that there is something here which is in a certain interpretation far more radical than most of the mainstream political discourses that we hear at the moment.

NS: You’re a literary scholar, and you’re talking about religion. Is religion literature? Are you proposing that religion become a resource for politics to draw from in the same way as any other literary canon might be?

TE: No, not at all. I think the whole movement to see religion as literature is a way of diffusing its radical content. It’s actually a way of evading certain rather unpleasant realities that it insists on confronting us with. One of the things that happened in the 19th century was that culture — literary and other kinds of culture — tried to stand in for religion, and there was a lot of talk about religion as poetry and religion as myth. That was an attempt to shy away from some of the more uncomfortable challenges of religion when taken rather more seriously.

NS: And those are the political challenges?

TE: Largely. Or, if you like, the ethical-political. They were forgotten, or sidelined, and Christianity in particular became a piece of poetry or a piece of mythology. There’s a lot of poetry and mythology in the Bible, to be sure, but it interacts with other kinds of elements, and that’s what I was stressing.

NS: Do you think that these traditions need to be radically reinterpreted for the modern, secular world? Thomas Aquinas is mentioned in your book, but so are — perhaps even more — Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. Is the religion you’re defending closer to that of the medieval scholastics or to these more recent figures?

TE: I think that the Christian gospel always stands in need of contemporary reinterpretation. Theologians have to determine what kind of discourse, what contemporary way of talking, can best articulate its particular concerns. There should be controversy and debate. While Marx and Freud and others are relevant to the contemporary interpretation of Christianity, that doesn’t mean one rejects tradition and simply concentrates on the present. The present is made out of tradition and out of history. What I’m offering in my book is what I take to be — although it’s couched very often in terms of Marx or Freud or radicalism in general — a fairly traditional interpretation of scripture.

NS: Though of course the Christianity you present doesn’t sound like a lot of the Christianity one hears in the public sphere, especially in the United States.

TE: I think partly that’s because a lot the authentic meanings of the New Testament have become ideologized or mythologized away. Religion has become a very comfortable ideology for a dollar-worshipping culture. The scandal of the New Testament — the fact that it backs what America calls the losers, that it thinks the dispossessed will inherit the kingdom of God before the respectable bourgeois — all of that has been replaced, particularly in the States, by an idolatrous version. I’m presently at a university campus where we proudly proclaim the slogan “God, Country, and Notre Dame.” I think they have to be told, and indeed I have told them, that God actually takes little interest in countries. Yahweh is presented in the Jewish Bible as stateless and nationless. He can’t be used as a totem or fetish in that way. He slips out of your grasp if you try to do so. His concern is with universal humanity, not with one particular section of it. Such ideologies make it very hard to get a traditional version of Christianity across.

NS: There are so many competing claims for supernatural revelation; some people say they adjudicate truth by the Bible, or by papal authority. How do you know one reliable supernatural tradition from another?

TE: Well, you have to argue about it on the basis of reason, and evidence, and analysis, and historical research. In that sense, theology is like any other intellectual discipline. You don’t know intuitively, and you certainly can’t claim to know dogmatically. You can’t simply, in a sectarian way, assert one tradition over another. I don’t think there’s any one template, any one set of guidelines, which will magically identity the correct view. Theology, like any other intellectual discipline, is a potentially endless process of argument. But that’s not to say that anything goes.

NS: One thing that stood out to me was your reassertion of liberation theology, which, for instance, the current pope repudiated when he was Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. He was concerned that hope for a worldly liberation through revolution would become a substitute for spiritual liberation through Christ.

TE: It would certainly be a big mistake to identify any particular human society with the kingdom of God. If any liberation theology were doing that, then it would be properly rebuked. I don’t think that’s why the pope is averse to it; he’s averse to it anyway because of its politics. It would be a grave mistake to think that we’re talking about the difference between a material revolution and a spiritual one. That would be the kind of gnosticism, or dualism, which Judaism and Christianity challenge. A socialist revolution is quite as spiritual as the fight for the kingdom of God is material.

NS: Do you consider yourself a Christian per se, or a person who happens to like and be inspired by Christianity?

TE: I don’t think the pope will consider me a Christian. I was brought up, of course, a Catholic. I suppose it was fortunate that around the time of the Vatican Council I encountered, just when I might have rejected a lot of it, a very challenging version of Christianity. I felt there was no need to reject it on political and intellectual grounds, because it was highly relevant and sophisticated and engaging. In a sense one doesn’t have much choice about these things. What I find is that heritage very deeply influences my work, and probably has more so over the last few years. Quite what my relation to it now is is hard to say. But that’s just a historical dilemma, a matter of how to understand oneself historically.

NS: When you talk about it being beyond choice — I’ve been interested to see how Richard Dawkins calls himself a “post-Christian atheist” and talks about celebrating Christmas.

TE: I think, actually, he’s a pre-Christian atheist, because he never understood what Christianity is about in the first place! That would be rather like Madonna calling herself post-Marxist. You’d have to read him first to be post-him. As I’ve said before, I think that Dawkins in particular makes such crass mistakes about the kind of claims that Christianity is making. A lot of the time, he’s either banging at an open door or he’s shooting at a straw target.

NS: You say he emphasizes a “propositional” account of religious faith above a “performative” one. But how far can one go believing in God performatively, through political acts, before it becomes a proposition?

TE: All performatives imply propositions. There’s no point in my operating a performative like, say, promising, or cursing, unless I have certain beliefs about the nature of reality: that there is indeed such an institution as promising, that I am able to perform it, and so on. The performative and the propositional work into each other. But it is a typically positivist kind of mistake to begin with the propositional, just as it would be for someone trying to analyze a literary text, which is basically a performance. Somebody who didn’t grasp that would be making a root-and-branch mistake about the kind of thing being confronted. These new atheists, and, indeed, the great majority of believers, have been conned rather falsely into a positivist or dogmatic theology, into believing that religion consists in signing on for a set of propositions.

NS: Are there political reasons behind this mistake?

TE: Dawkins and I were recently asked to write articles for the front page of the Wall Street Journal, if you can believe it. I don’t know what the rationale behind this is, or even if it will come off. I said that I would do so, provided that my last sentence would be, “Jesus Christ would never have been given a column in the Wall Street Journal.” It is indicative of the strangeness and intensity of this debate that it crops up in the most peculiar places. It crops up at the very temples of Mammon. But, you see, I think that’s because these people really do think it’s just about a set of ideas, of propositions. That’s a pretty comfortable debate. But the point I try to make when I enter on these forums is that it’s not just that. It has a strong political subtext.

NS: Back to issues of faith and reason — your position reminds me of Stephen Jay Gould’s model of “non-overlapping magisteria.” Gould himself was not a believer, though he wrote about religion and science, and sometimes he has been accused of having a position that is only possible if you’re not really taking belief seriously.

TE: I think that Gould was right in that particular position. What is interesting is why it makes people like Dawkins so nervous. They misinterpret that position to mean that theology doesn’t have to conform to the rules and demands of reason. Then theologians can say anything they like. They don’t have to produce evidence, and they don’t have to engage in reasonable argument. They’re now released from the tenets of science. Traditionally, this is the Christian heresy known as fideism. But all kinds of rationalities, theology included, have been non-scientific for a very long time and yet still have to conform to the procedures of reason. The new atheists think this because they falsely identify the rules of reason with the rules of scientific reason. Therefore if something is outside the purview of science, it follows for them that it is outside the purview of reason itself. But that’s a false way of arguing. Dawkins won’t entertain either the idea that faith must engage reason or that the very idea of what rationality is is to be debated.

NS: The atheists have promoted themselves by wearing big red “A”s on their t-shirts and calling themselves “brights.” Is there a counter-movement you’d like to begin? What would you put on the t-shirt?

TE: Rather than simply man the barricades on either side, I’d like to step back and see what’s happening here. That sort of gesture has to be understood in terms of an American society in which a relatively small coterie of self-consciously enlightened atheists or agnostics are indeed confronted with a massively ideologized religion, which in many respects is very ugly indeed. What I think is wrong, and what I think is rationalistic, is to cast the argument in terms of intelligence. It may be that a lot of people who believe that they’re going to be rapt up into heaven are fairly dim creatures. On the other hand, Europe is full of dim agnostics. It is a rationalist error to think that your opponents are simply stupid. That betrays what’s wrong with this particular kind of new atheism: it casts the arguments largely in intellectual and propositional terms and doesn’t see that a great deal else is involved here.

NS: Do you think that it’s an accident that the most successful of the new atheists, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, come with English accents?

TE: No. England is a very agnostic society. It looks with amazement on the behavior of many Americans as far as religion goes. America, of course, is in all kinds of ways out of line. It’s still an enormously metaphysical and religious society, while the typical advanced capitalist culture is pretty skeptical. Advanced capitalist societies do not normally call upon their citizens to believe very much, as long as they roll out of bed and do their work. They are pretty post-metaphysical. In a sense, Britain is a post-metaphysical society. A very small minority of people go to church. Religion is not part of a public and political discourse in anything like the way it is in the States. The States is peculiar because it is, on the one hand, the most rampantly capitalist society in history and, on the other, deeply, deeply metaphysical. Really, those two things are inherently at odds. Markets are relativizing, pragmatizing, and secularizing. But to prop them up, to defend them, and to legitimate them, you may need some much more absolute values. That may be why there are a lot of psycho-spiritual stockbrokers around.

This interview was first published in The Immanent Frame on 17 September 2009; it is reproduced here for educational purposes.

Literary critic Terry Eagleton discusses his new book, Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate, which argues that “new atheists” like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens “buy their rejection of religion on the cheap.” He believes that, in these controversies, politics has been an unacknowledged elephant in the room.

Nathan Schneider: Rather than focusing on “believers” or “atheists,” which are typically the categories that we hear about in the new atheist debates, you write about “a version of the Christian gospel relevant to radicals and humanists.” Who are these people? Why do you choose to address them?

Terry Eagleton: I wanted to move the arguments beyond the usual, rather narrow circuits in order to bring out the political implications of these arguments about God, which hasn’t been done enough. We need to put these arguments in a much wider context. To that extent, in my view, radicals and humanists certainly should be in on the arguments, regardless of what they think about God. The arguments aren’t just about God or just about religion.

NS: Are you urging people to go to church, or to read the Bible, or simply to acknowledge the historical connections between, say, Marxism and Christianity?

TE: I’m certainly not urging them to go to church. I’m urging them, I suppose, to read the Bible because it’s very relevant to radical political concerns. In many ways, I agree with someone like Christopher Hitchens that most religion is fairly hideous and purely ideological. But I think that Hitchens and Richard Dawkins are gravely one-sided about the issue. There are other potentials in the gospel and in the Christian tradition which are, or should be, of great interest to radicals, and radicals haven’t sufficiently recognized that. I’m not trying to convert anybody, but I am trying to show them that there is something here which is in a certain interpretation far more radical than most of the mainstream political discourses that we hear at the moment.

NS: You’re a literary scholar, and you’re talking about religion. Is religion literature? Are you proposing that religion become a resource for politics to draw from in the same way as any other literary canon might be?

TE: No, not at all. I think the whole movement to see religion as literature is a way of diffusing its radical content. It’s actually a way of evading certain rather unpleasant realities that it insists on confronting us with. One of the things that happened in the 19th century was that culture — literary and other kinds of culture — tried to stand in for religion, and there was a lot of talk about religion as poetry and religion as myth. That was an attempt to shy away from some of the more uncomfortable challenges of religion when taken rather more seriously.

NS: And those are the political challenges?

TE: Largely. Or, if you like, the ethical-political. They were forgotten, or sidelined, and Christianity in particular became a piece of poetry or a piece of mythology. There’s a lot of poetry and mythology in the Bible, to be sure, but it interacts with other kinds of elements, and that’s what I was stressing.

NS: Do you think that these traditions need to be radically reinterpreted for the modern, secular world? Thomas Aquinas is mentioned in your book, but so are — perhaps even more — Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. Is the religion you’re defending closer to that of the medieval scholastics or to these more recent figures?

TE: I think that the Christian gospel always stands in need of contemporary reinterpretation. Theologians have to determine what kind of discourse, what contemporary way of talking, can best articulate its particular concerns. There should be controversy and debate. While Marx and Freud and others are relevant to the contemporary interpretation of Christianity, that doesn’t mean one rejects tradition and simply concentrates on the present. The present is made out of tradition and out of history. What I’m offering in my book is what I take to be — although it’s couched very often in terms of Marx or Freud or radicalism in general — a fairly traditional interpretation of scripture.

NS: Though of course the Christianity you present doesn’t sound like a lot of the Christianity one hears in the public sphere, especially in the United States.

TE: I think partly that’s because a lot the authentic meanings of the New Testament have become ideologized or mythologized away. Religion has become a very comfortable ideology for a dollar-worshipping culture. The scandal of the New Testament — the fact that it backs what America calls the losers, that it thinks the dispossessed will inherit the kingdom of God before the respectable bourgeois — all of that has been replaced, particularly in the States, by an idolatrous version. I’m presently at a university campus where we proudly proclaim the slogan “God, Country, and Notre Dame.” I think they have to be told, and indeed I have told them, that God actually takes little interest in countries. Yahweh is presented in the Jewish Bible as stateless and nationless. He can’t be used as a totem or fetish in that way. He slips out of your grasp if you try to do so. His concern is with universal humanity, not with one particular section of it. Such ideologies make it very hard to get a traditional version of Christianity across.

NS: There are so many competing claims for supernatural revelation; some people say they adjudicate truth by the Bible, or by papal authority. How do you know one reliable supernatural tradition from another?

TE: Well, you have to argue about it on the basis of reason, and evidence, and analysis, and historical research. In that sense, theology is like any other intellectual discipline. You don’t know intuitively, and you certainly can’t claim to know dogmatically. You can’t simply, in a sectarian way, assert one tradition over another. I don’t think there’s any one template, any one set of guidelines, which will magically identity the correct view. Theology, like any other intellectual discipline, is a potentially endless process of argument. But that’s not to say that anything goes.

NS: One thing that stood out to me was your reassertion of liberation theology, which, for instance, the current pope repudiated when he was Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. He was concerned that hope for a worldly liberation through revolution would become a substitute for spiritual liberation through Christ.

TE: It would certainly be a big mistake to identify any particular human society with the kingdom of God. If any liberation theology were doing that, then it would be properly rebuked. I don’t think that’s why the pope is averse to it; he’s averse to it anyway because of its politics. It would be a grave mistake to think that we’re talking about the difference between a material revolution and a spiritual one. That would be the kind of gnosticism, or dualism, which Judaism and Christianity challenge. A socialist revolution is quite as spiritual as the fight for the kingdom of God is material.

NS: Do you consider yourself a Christian per se, or a person who happens to like and be inspired by Christianity?

TE: I don’t think the pope will consider me a Christian. I was brought up, of course, a Catholic. I suppose it was fortunate that around the time of the Vatican Council I encountered, just when I might have rejected a lot of it, a very challenging version of Christianity. I felt there was no need to reject it on political and intellectual grounds, because it was highly relevant and sophisticated and engaging. In a sense one doesn’t have much choice about these things. What I find is that heritage very deeply influences my work, and probably has more so over the last few years. Quite what my relation to it now is is hard to say. But that’s just a historical dilemma, a matter of how to understand oneself historically.

NS: When you talk about it being beyond choice — I’ve been interested to see how Richard Dawkins calls himself a “post-Christian atheist” and talks about celebrating Christmas.

TE: I think, actually, he’s a pre-Christian atheist, because he never understood what Christianity is about in the first place! That would be rather like Madonna calling herself post-Marxist. You’d have to read him first to be post-him. As I’ve said before, I think that Dawkins in particular makes such crass mistakes about the kind of claims that Christianity is making. A lot of the time, he’s either banging at an open door or he’s shooting at a straw target.

NS: You say he emphasizes a “propositional” account of religious faith above a “performative” one. But how far can one go believing in God performatively, through political acts, before it becomes a proposition?

TE: All performatives imply propositions. There’s no point in my operating a performative like, say, promising, or cursing, unless I have certain beliefs about the nature of reality: that there is indeed such an institution as promising, that I am able to perform it, and so on. The performative and the propositional work into each other. But it is a typically positivist kind of mistake to begin with the propositional, just as it would be for someone trying to analyze a literary text, which is basically a performance. Somebody who didn’t grasp that would be making a root-and-branch mistake about the kind of thing being confronted. These new atheists, and, indeed, the great majority of believers, have been conned rather falsely into a positivist or dogmatic theology, into believing that religion consists in signing on for a set of propositions.

NS: Are there political reasons behind this mistake?

TE: Dawkins and I were recently asked to write articles for the front page of the Wall Street Journal, if you can believe it. I don’t know what the rationale behind this is, or even if it will come off. I said that I would do so, provided that my last sentence would be, “Jesus Christ would never have been given a column in the Wall Street Journal.” It is indicative of the strangeness and intensity of this debate that it crops up in the most peculiar places. It crops up at the very temples of Mammon. But, you see, I think that’s because these people really do think it’s just about a set of ideas, of propositions. That’s a pretty comfortable debate. But the point I try to make when I enter on these forums is that it’s not just that. It has a strong political subtext.

NS: Back to issues of faith and reason — your position reminds me of Stephen Jay Gould’s model of “non-overlapping magisteria.” Gould himself was not a believer, though he wrote about religion and science, and sometimes he has been accused of having a position that is only possible if you’re not really taking belief seriously.

TE: I think that Gould was right in that particular position. What is interesting is why it makes people like Dawkins so nervous. They misinterpret that position to mean that theology doesn’t have to conform to the rules and demands of reason. Then theologians can say anything they like. They don’t have to produce evidence, and they don’t have to engage in reasonable argument. They’re now released from the tenets of science. Traditionally, this is the Christian heresy known as fideism. But all kinds of rationalities, theology included, have been non-scientific for a very long time and yet still have to conform to the procedures of reason. The new atheists think this because they falsely identify the rules of reason with the rules of scientific reason. Therefore if something is outside the purview of science, it follows for them that it is outside the purview of reason itself. But that’s a false way of arguing. Dawkins won’t entertain either the idea that faith must engage reason or that the very idea of what rationality is is to be debated.

NS: The atheists have promoted themselves by wearing big red “A”s on their t-shirts and calling themselves “brights.” Is there a counter-movement you’d like to begin? What would you put on the t-shirt?

TE: Rather than simply man the barricades on either side, I’d like to step back and see what’s happening here. That sort of gesture has to be understood in terms of an American society in which a relatively small coterie of self-consciously enlightened atheists or agnostics are indeed confronted with a massively ideologized religion, which in many respects is very ugly indeed. What I think is wrong, and what I think is rationalistic, is to cast the argument in terms of intelligence. It may be that a lot of people who believe that they’re going to be rapt up into heaven are fairly dim creatures. On the other hand, Europe is full of dim agnostics. It is a rationalist error to think that your opponents are simply stupid. That betrays what’s wrong with this particular kind of new atheism: it casts the arguments largely in intellectual and propositional terms and doesn’t see that a great deal else is involved here.

NS: Do you think that it’s an accident that the most successful of the new atheists, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, come with English accents?

TE: No. England is a very agnostic society. It looks with amazement on the behavior of many Americans as far as religion goes. America, of course, is in all kinds of ways out of line. It’s still an enormously metaphysical and religious society, while the typical advanced capitalist culture is pretty skeptical. Advanced capitalist societies do not normally call upon their citizens to believe very much, as long as they roll out of bed and do their work. They are pretty post-metaphysical. In a sense, Britain is a post-metaphysical society. A very small minority of people go to church. Religion is not part of a public and political discourse in anything like the way it is in the States. The States is peculiar because it is, on the one hand, the most rampantly capitalist society in history and, on the other, deeply, deeply metaphysical. Really, those two things are inherently at odds. Markets are relativizing, pragmatizing, and secularizing. But to prop them up, to defend them, and to legitimate them, you may need some much more absolute values. That may be why there are a lot of psycho-spiritual stockbrokers around.

This interview was first published in The Immanent Frame on 17 September 2009; it is reproduced here for educational purposes.

Δευτέρα 26 Δεκεμβρίου 2011

Badiou: On Christian Eschatology (Via Q Meillassoux)

Πηγή: Metastable Equilibrium

In conclusion, one can wonder about the disconcerting bond between the Badiousian conception of a truth and the Christian conception of the Incarnation. In EE, meditation 21 devoted to Pascal opens on thought 776 (éd. Lafuma): "The history of the Church must properly be called the history of truth". And in fact, one can say that Badiou accords to Pascal to have seized, and with him Pauline Christianity, to which was expressly devoted a book, that which one could call the "genuine proceedings of the truth". Because if Christianity is founded on a fable, according to Badiou, its force comes from having seized if not its contents then at least the real form of any truth: it proceeds by way of a event not demonstrable by a constituted knowledge - the divinity of Christ - of which one would know more than the trace - the testimony of apostles, of evangelists, etc., but its being is already abolished, crucified, and even its body has already disappeared, while the belief starts to emerge that it will have taken place. And the Christian truth is the ensemble of enquiries of fidelities, i.e. their intervention in the Palestinian situation, then Middle-Eastern and Roman, in the light of their having held the place of Christianity. Lastly, universal history, for the Christians, is nothing other than the ensemble of enquiries of the Church-subject over the course of centuries, made of schisms and heresies, therefore of research into the formula and action of a fidelity to the absolute event of man's divine creation. Out the Church, not of history, and not of hello, only the monotonous chaos of passions and perditions.

Badiou is thus here in extreme fidelity... - with the structure, if not the contents - of Christian eschatology. It is by no means the denial of this dream, as it is he who makes of Paul the "founder of universalism": that which seized the first militant nature, and not the erudition, of truth. In this sense it without doubt represents one of the possible evolutions of Marxism, shared since the beginning between critical thought and revolutionary eschatology. A great part of the ex-Marxists renounced eschatology, considering that it was effectively religious residue, a principal source among the promethean disasters of real socialism. The singularity of Badiou seems on the contrary to consist of this: that he isolates from Marxism its eschatologic share, separates it from its pretension, that he considers economic scientificity illusory, and delivers it, burning, on the disseminated subjects of all kinds of struggles, political as well as amorous. With the place of the religious illusion of eschatology dissolved by criticism in the writings of Badiou, eschatology becomes irreligious so that the event can deploy its critical power on the colorless present of our ordinary renouncements.

Ολο το κείμενο εδώ

In conclusion, one can wonder about the disconcerting bond between the Badiousian conception of a truth and the Christian conception of the Incarnation. In EE, meditation 21 devoted to Pascal opens on thought 776 (éd. Lafuma): "The history of the Church must properly be called the history of truth". And in fact, one can say that Badiou accords to Pascal to have seized, and with him Pauline Christianity, to which was expressly devoted a book, that which one could call the "genuine proceedings of the truth". Because if Christianity is founded on a fable, according to Badiou, its force comes from having seized if not its contents then at least the real form of any truth: it proceeds by way of a event not demonstrable by a constituted knowledge - the divinity of Christ - of which one would know more than the trace - the testimony of apostles, of evangelists, etc., but its being is already abolished, crucified, and even its body has already disappeared, while the belief starts to emerge that it will have taken place. And the Christian truth is the ensemble of enquiries of fidelities, i.e. their intervention in the Palestinian situation, then Middle-Eastern and Roman, in the light of their having held the place of Christianity. Lastly, universal history, for the Christians, is nothing other than the ensemble of enquiries of the Church-subject over the course of centuries, made of schisms and heresies, therefore of research into the formula and action of a fidelity to the absolute event of man's divine creation. Out the Church, not of history, and not of hello, only the monotonous chaos of passions and perditions.

Badiou is thus here in extreme fidelity... - with the structure, if not the contents - of Christian eschatology. It is by no means the denial of this dream, as it is he who makes of Paul the "founder of universalism": that which seized the first militant nature, and not the erudition, of truth. In this sense it without doubt represents one of the possible evolutions of Marxism, shared since the beginning between critical thought and revolutionary eschatology. A great part of the ex-Marxists renounced eschatology, considering that it was effectively religious residue, a principal source among the promethean disasters of real socialism. The singularity of Badiou seems on the contrary to consist of this: that he isolates from Marxism its eschatologic share, separates it from its pretension, that he considers economic scientificity illusory, and delivers it, burning, on the disseminated subjects of all kinds of struggles, political as well as amorous. With the place of the religious illusion of eschatology dissolved by criticism in the writings of Badiou, eschatology becomes irreligious so that the event can deploy its critical power on the colorless present of our ordinary renouncements.

Ολο το κείμενο εδώ

Γ.Βαρδαβας:Βιβλιοπαρουσίαση του Terry Eagleton, Λογική, Πίστη και Επανάσταση

Ο Terry Eagleton δεν χρειάζεται συστάσεις. Είναι γνωστό ότι πρόκειται για έναν από τους μεγαλύτερους σύγχρονους διανοούμενους. Στο νέο του βιβλίο Λογική Πίστη και Επανάσταση ο Eagleton καθηλώνει τον αναγνώστη όχι μόνο με την αντικειμενικότητα και την ευρυμάθεια του, αλλά κυρίως διότι λέει αλήθειες. Αλήθειες που ενοχλούν εκατέρωθεν (ενθέους και αθέους), αλλά αλήθειες αμείλικτες. Απέναντι σε έναν άκρατο επιστημονικό θετικισμό με έντονο δογματισμό και επιδερμική απλοϊκότητα (τύπου Dawkins) ο Eagleton προτείνει μια ριζοσπαστική ανάγνωση του χριστιανισμού, καταδικάζοντας ταυτόχρονα τη θεσμική του έκφραση για προδοσία έναντι των ριζοσπαστικών του καταβολών. Στη διελκυστίνδα πίστης και επιστήμης παρεμβάλλεται η πολιτική:

Το διακύβευμα εν προκειμένω δεν είναι κάποιο συνετά αναμορφωτικό πρόγραμμα, τύπου έγχυσης καινούργιου κρασιού σε παλιά μπουκάλια, αλλά μια πρωτοποριακή αποκάλυψη του απολύτως νέου – ενός καθεστώτος τόσο επαναστατικού, που υπερβαίνει κάθε εικόνα και λόγο, μιας ηγεμονίας της δικαιοσύνης και της αδελφοσύνης που κατά τους περί τα Ευαγγέλια γράφοντες εντυπωσιάζει ακόμη και σήμερα μέσα σε αυτόν τον χρεοκοπημένο, depasse, ναυαγισμένο κόσμο. Καμία μέση οδός δεν επιτρέπεται εδώ: η επιλογή μεταξύ της δικαιοσύνης και των εξουσιών αυτού του κόσμου δεν μπορεί παρά να είναι ξεκάθαρη και απόλυτη, ζήτημα θεμελιακής σύγκρουσης και αντίθεσης. Εδώ το ζητούμενο είναι ένα κοφτερό σπαθί, όχι ειρήνη, συναίνεση και διαπραγμάτευση. Ο Ιησούς δεν φέρνει ούτε κατά διάνοια σε φιλελεύθερο, κάτι που αναμφίβολα του το κρατάει ο Ντίτσκινς*. Δεν θα γινόταν καλό μέλος επιτροπής. Ούτε θα τα πήγαινε καλά στη Γουόλ Στριτ, όπως δεν τα πήγε καλά με τα γραφεία συναλλάγματος στον ναό της Ιερουσαλήμ. (Eagleton,μν.εργ.,σελ. 45).

Η αναμέτρηση με τη σκέψη του Eagleton δεν θα είναι εύκολη για όσους εμμένουν στις “βεβαιότητες” τους (ένθεοι ή άθεοι, αδιάφορον). Παραθέτουμε ένα “νόστιμο” τμήμα από την κριτική του Eagleton στον Dawkins:

Επειδή η ύπαρξη του κόσμου δεν υπόκειται σε καμία αναγκαιότητα, δεν μπορούμε να συναγάγουμε τους νόμους που τον κυβερνούν από απριορικές αρχές, αλλά πρέπει να κοιτάξουμε το πως λειτουργεί στην πραγματικότητα. Αυτό είναι έργο της επιστήμης. Υπάρχει λοιπόν μια περίεργη σχέση ανάμεσα στο δόγμα της δημιουργίας από το τίποτα και στον επαγγελματικό βίο του Ρίτσαρντ Ντόκινς. Χωρίς τον Θεό ο Ντόκινς θα ήταν άνεργος. Οπότε είναι άκρως αγενές εκ μέρους του το να αμφισβητεί την ύπαρξη του εργοδότη του.(T. Eagleton, μν. έργον,σελ. 26-27).

Εξαιρετικό ενδιαφέρον παρουσιάζει ο τρόπος που ο Eagleton ορίζει την πίστη:

Οι άνθρωποι καλούνται να μην κάνουν τίποτα περισσότερο από το να αναγνωρίσουν, μέσα από την πράξη της αγαπητικής συγκατάνευσης που ονομάζεται πίστη, το γεγονός ότι ο Θεός είναι με το μέρος τους ό,τι κι αν γίνει. Ο Ιησούς δεν έχει στην πραγματικότητα παρά ελάχιστα πράγματα να πει γύρω από την αμαρτία, αντίθετα με πλήθος φιλοκατήγορων οπαδών του. Η αποστολή του είναι να αποδεχτεί την αδυναμία των ανθρώπων, όχι να τους την τρίψει στη μούρη. (μν. εργ., σελ. 41).

Η εν λόγω ριζοσπαστική “ανάγνωση” του Eagleton δεν σημαίνει ότι αποστασιοποιείται από τις θεμελιακές μαρξιστικές καταβολές του. Στον Πρόλογο του βιβλίου ασκεί σκληρή κριτική στη θρησκεία: “Η θρησκεία έχει επιφέρει ανείπωτη εξαθλίωση στα ανθρώπινα πράγματα. Ως επί το πλείστον έχει υπάρξει μια βρομερή ιστορία μισαλλοδοξίας, δεισιδαιμονίας, ευσεβών πόθων και καταπιεστικής ιδεολογίας” (μν.εργ.,σελ.11). Ωστόσο ασκεί δριμύτατη κριτική και σε όσους επικριτές της “αγοράζουν την απόρριψη της θρησκείας σε τιμή ευκαιρίας” , ενώ οι ίδιοι “διακατέχονται από τόσο βαθιά άγνοια και προκατάληψη ώστε να συναγωνίζονται τη θρησκεία” (ό.π.).

Ας δούμε τι λέει ο Eagleton περί χριστιανικής αγάπης:

Κατά τη χριστιανική διδασκαλία η αγάπη και η συγχώρεση του Θεού είναι αδίστακτα ανελέητες δυνάμεις, που ξεσπούν βίαια επάνω στην προστατευτική, αυτοεκλογικευτική μικρή μας σφαίρα, διαλύοντας τις συναισθηματικές ψευδαισθήσεις μας και αναποδογυρίζοντας βάναυσα τον κόσμο μας (…)(…)Αν δεν αγαπάς είσαι νεκρός κι αν αγαπάς θα σε σκοτώσουν. Ορίστε λοιπόν η επαγγελία των παραδείσιων απολαύσεων ή το όπιο των μαζών, η παρηγοριά σας του γλυκού βλέμματος και η ευλάβεια των χλωμών παρειών.(…)(μν.έργ.,σελ. 43-44)

Είναι τόσο πλούσια η θεματική του βιβλίου που σε κάθε σελίδα του ο αναγνώστης θα βρει κάτι που θα τον ενθουσιάσει, θα τον προβληματίσει ή μπορεί και να τον εκνευρίσει. Έτσι είναι όμως τα μεγάλα έργα. Κλείνοντας τη μικρή αυτή παρουσίαση νομίζουμε ότι αξίζει ο αναγνώστης να δει πως ορίζει ο Eagleton την “οικτρή κατάσταση”(σελ. 46) αλλά και το “μαρτύριο”(σελ. 48).

Σημ.: Οι ανωτέρω επισημάνσεις αφορούν το πρώτο κεφάλαιο του βιβλίου (“Τα αποβράσματα της Γης”, σελ. 17-72). Μια αναλυτική διαπραγμάτευση θα απαιτούσε πάρα πολύ χώρο. Σε τελική ανάλυση, έργα τέτοιας αξίας απαιτούν όχι μόνο την προσοχή, αλλά και την άμεση μετοχή του αναγνώστη στο βαθυστόχαστο περιεχόμενο τους.

——————————

*[Πρόκειται για παιγνιώδη σύμπτυξη των επωνύμων Ντόκινς-Χίτσενς από το συγγραφέα "χάριν ευκολίας"(μν. έργον, σελ. 19) ].

25-12-2011

Γ.Μ.Βαρδαβάς

Σάββατο 10 Δεκεμβρίου 2011

Το μυστήριο της οικονομίας :η Οικονομική Θεολογία στον G.Agamben

Τι ειδους ακριβώς είναι επιστημη είναι η οικονομία;Η συζήτηση δεν είναι καινούργια ,και δεν πρόκειται να τελειώσει ποτέ .Το επιδικο της συζήτησης είναι το ίδιο με καθε κοινωνική επιστήμη .Ο παρατηρητής είναι μέρος του αντικειμένου του.Άρα όσο και αν υιοθετηθούν διαδικασίες και πρότυπα ορθολογισμου , θα υπάρχει πάντα ένα μικρο η μεγάλο ποσοστό αβεβαιότητας και σχετικισμου.Χοντρικά οι " δεξιοί " αποδίδουν τις αβεβαιότητες στην ίδια την φύση των σύγχρονων κοινωνιών ενω οι " αριστεροί " στην ιδεολογική φύση των μοντέλων της οικονομίας .Δεν είναι τυχαίο πως εντος αριστεράς αναδύονται οι πιο ριζικές απόψεις κριτικής της πολιτικής οικονομίας που φτάνουν την ολική άρνηση ακόμη και της μαρξιστικης οπτικής (Badiou).Η συζήτηση μάλλον θα διαρκέσει όσο αυτη για την φύση του φωτοστεφανου.

Ωστόσο υπάρχει και μια ενδιαφέρουσα οπτική , η οποία δεν εξετάζει την οικονομία με βάση ένα κριτήριο επιστημολογικης η ιδεολογικής κατασκευής .Η οπτική αυτή εκκινεί απο το δεδομένο ότι οικονομία είτε ως κοινωνική επιστήμη ,με αξιώσεις ορθολογισμου, είτε ως υποκειμενική ιδεολογική άσκηση και πρακτική έχει μια άρθρωση με την εξουσία. Το ερώτημα λοιπον που τίθεται είναι πως, η με οποιοδήποτε τροπο οριζομενη οικονομία, σχετίζεται με την εξουσία και την διακυβέρνηση στις σύγχρονες κοινωνίες.Το ζήτημα δεν τίθεται στο να αποκαλύψουμε την " διαπλοκή" η την ταξική φύση των καπιταλιστικών σχέσεων οι οποίες εμφανίζονται ως φυσικές ,αλλά στο πως η οικονομία παραμένει μονίμως ως ένας πόλος σε σχέση και απόσταση απο τη διακυβέρνηση .Η οικονομία σε καμία περίπτωση δεν είναι απλά " κατω" απο την διακυβέρνηση . Αντανακλά και σχηματοποιει ταξικές σχέσεις αλλα μονίμως είναι σε μια ένταση με την εξουσία .

Τον προβληματισμό αυτο αναπτύσσει ο G.Agamben στο τριτο μέρος του Homo Sacer " Il Regno e la Gloria" .Στο έργο αυτο ο GA προχωρά και εξελίσσει την θεματολογία της Πολιτικής Θεολογίας προς μια θεματολογία Οικονομικής Θεολογίας .Αν η Πολιτικη Θεολογια στηρίζεται στην θέση οτι οι σύγχρονες πολιτικές έννοιες προέρχονται απο της Θεολογία, η Οικονομική Θεολογία στηριζεται στην θεση ότι η σχέση εξουσίας οικονομίας έχει τη μορφή της τριαδικης υπόστασης του Θεού . Εκκεντρικό θεωρημα ίσως , αλλα για αυτο ο GA αφιερώνει διακόσιες πυκνες σελίδες .

Χοντρικά η εξέταση του GA είναι η ακόλουθη:

Όταν η χριστιανική Θεολογία αναπτύσσει την έννοια της τριαδικης υπόστασης, για να μην περιπέσει ουσιαστικά σε ένα τριθεισμό ,εισάγει εντος θεολογίας μια έννοια εκτός αυτής : την έννοια της αριστοτελικης οικονομίας .Με την εισαγωγή της έννοιας της οικονομίας οι τρεις υποστασεις του θείου συγκροτούνται σε μια δυναμική σχέση .Παράγωγες της τριαδικης υπόστασης είναι οι εννοιες της θειας πρόνοιας και η ανάγκη εισαγωγής της κατηγορίας, του συνόλου των αγγέλων .

Σύμφωνα με τον GA η αριστοτελικη οικονομία δεν είναι επιστήμη , αλλα πράξις. Δεν ορίζει ένα δομημένο τομέα έρευνας και ανάλυσης αλλα είναι διεκπεραίωση , διαδικασία ,πράξη.Η οικονομία είναι διαχείριση του οίκου σε αντιδιαστολή με την πολιτικη που είναι διαχείριση των της πόλης.Αυτη λοιπόν έννοια της οικονομίας εισάγεται στην Θεολογία για να σχηματοποιηθει το δυναμικό πλάσμα του τριαδικου θεού.

Το ενδιαφέρον που αποκαλύπτει ο GΑ ,μεσω μιας ενδελεχούς ιστορικής έρευνας ,είναι ότι αυτή η θεολογική οικονομία " επανεξαγεται " απο την Θεολογία προς την οικονομία των φυσιοκρατών δεκαπέντε αιώνες μετά. Το ιστορικό σχημα είναι περίπου το εξής:

Η Χριστιανικη Θεολογία έχει ανάγκη την έννοια της οικονομίας για να μην παλινδρομησει σε πολυθεϊσμό , την εισάγει στην τριαδικη υπόσταση, και αυτήν την θεολογική " οικονομία " διαχειρίζονται οι φυσιοκράτες για να να εξελιξουμε ως τις μέρες μας ως επιστήμη.Για να κατανοήσουμε λοιπον τις συγχρονες σχέσεις οικονομίας εξουσίας δεν έχουμε παρά να δούμε τις σχέσεις Θεού Υιού στο τριαδικό πλέγμα .

Η σημερινή οικονομία δεν είναι ουτε αυστηρή επιστήμη ούτε στεγνή πράξη , είναι μυστηριώδης όσο αναλογικά είναι μυστηριώδες το τριαδικό θεολογικο σχήμα το οποίο διαχωρίζει τον Θεό απο τις Πράξεις του.Ο GA προχωρεί ένα βήμα παραπάνω και διακρίνει στις μεγάλες διαμάχες του κατά του Μονοθεισμου μια κρίσιμη στροφή που επικυρωνει τον θεμελιακό δυϊσμό ,Θεού και Θείας Οικονομίας η οποία συγκροτεί και το μυστήριο της οικονομίας .Η άναρχη ισότιμη σχέση Θεού Υιου συγκροτεί ένα πεδίο πράξεων που δεν έχουν γραμμικη σχέση εκπορευσης απο το ένα του Θεού, αλλα αναδύονται εκ θεού ως μια ειδική θεία τυχαιοτητα . Αυτη την μυστηριώδη τυχαιοτητα αποκρυσταλλώνει η οικονομία .

Αν στο κλασικό σχήμα της πολιτικής θεολογίας του C Smitt η πολιτική εξουσία προέρχεται , καθρεφτίζεται, αναδύεται ως η μεταφορά του Θεού ,το κράτος έκτακτης ανάγκης ως το θαύμα κλπ κλπ στον G.Agamben η οικονομία αναβιώνει το δυναμικό σχήμα της τριαδικοτητας.Απο εκεί και πέρα αναπτύσσεται μια θεματολογία με εξαιρετική ευρηματικότητα και πρωτοτυπία .πχ όλη η σχετική Θεολογία των Αγγέλων ορίζεται απο τον GA ως η μήτρα μιας σχετικής σύγχρονης εξέτασης της γραφειοκρατία.Καλός ο Weber αλλά για να δούμε και τον Ακινάτη.....Στο ίδιο το βιβλίο του GA διαμορφώνεται με μια άλλη γιγάντια μεταφορά η οποία εξετάζει τις σχέσεις οικονομίας και οψης- θεάματος της εξουσίας , σε αντιστοιχία με τις σχέσεις τριαδικοτητας και δοξολογιας.Αυτο όμως είναι ένα άλλο εκκεντρικό θέμα ,άξιο ενός αλλού μικρού σχολιασμού.

Παρέκβαση : Ο Agamben και η αριστερά

Ο G.Agamben είναι προφανώς ένας απο τους πιο σημαντικούς σύγχρονους πολιτικούς φιλόσοφους με οξύ κριτικό προσανατολισμός.Ωστόσο όντας μαθητής του Heidegger δεν ανήκει τυπικά στο Χεγκελιανο Μαρξιστικο ρεύμα της Αριστεράς.Με μια έννοια η κριτική του είναι εξαιρετικά απαισιόδοξη, σχεδόν αποπνικτική . Το φράγμα αυτο , αυτήν την ορατή απόσταση , αποτυπώνει καθαρά ο διάλογος Negri Agamben όπως διεξάγεται τα τελευταία χρονιά .Είναι προφανώς αδύνατο αυτη η διαμάχη να αποτυπωθεί σε μια γραμμή ωστόσο χοντρικά μπορούμε να πούμε πως αν η " γυμνή ζωή " αποτελεί ένα όριο για τον GA με βάση την έννοια κλειδι του Homo Sacer ,στον ΑΝ η γυμνή ζωή δεν είναι όριο αλλα παραγωγή.Περισσότερα εδώ .Η σημείωση είναι απαραίτητη για να κατανοηθεί η πολιτικη Θεολογία του GA , και εισαγωγή του όρου της Οικονομικής Θεολογίας . Όπως και σε όλο το έργο του , η κριτική του είναι οξεία , διαβρωτική αλλά οι διέξοδοι που αναδύονται είτε είναι ελάχιστα ορατοί είτε σχεδόν εσχατολογικοί ( πχ Η κοινότητα που έρχεται )

Συνδέσεις:

Πυκνή παρουσιάση του ιδιου του Agamben για το "Il Regno e la Gloria " εδώ

G.Agamben : The Kingdom and the Glory (amazon)

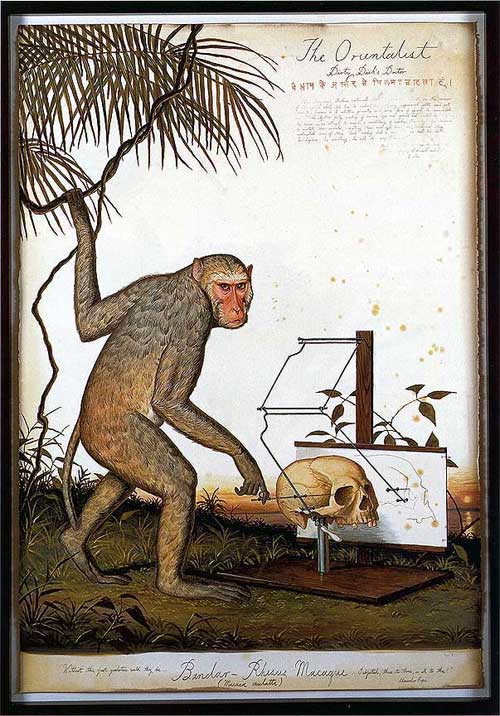

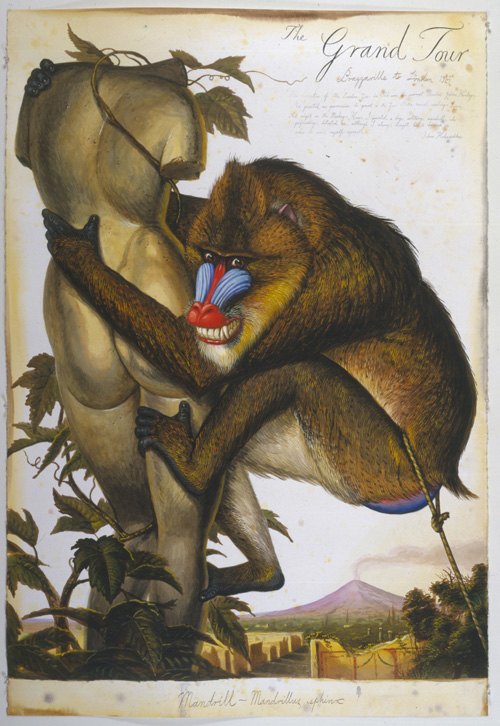

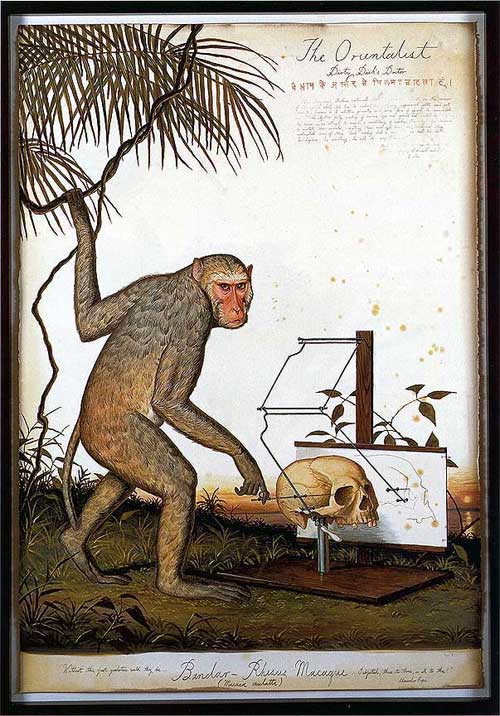

Εικόνα : Dino Valls

Ωστόσο υπάρχει και μια ενδιαφέρουσα οπτική , η οποία δεν εξετάζει την οικονομία με βάση ένα κριτήριο επιστημολογικης η ιδεολογικής κατασκευής .Η οπτική αυτή εκκινεί απο το δεδομένο ότι οικονομία είτε ως κοινωνική επιστήμη ,με αξιώσεις ορθολογισμου, είτε ως υποκειμενική ιδεολογική άσκηση και πρακτική έχει μια άρθρωση με την εξουσία. Το ερώτημα λοιπον που τίθεται είναι πως, η με οποιοδήποτε τροπο οριζομενη οικονομία, σχετίζεται με την εξουσία και την διακυβέρνηση στις σύγχρονες κοινωνίες.Το ζήτημα δεν τίθεται στο να αποκαλύψουμε την " διαπλοκή" η την ταξική φύση των καπιταλιστικών σχέσεων οι οποίες εμφανίζονται ως φυσικές ,αλλά στο πως η οικονομία παραμένει μονίμως ως ένας πόλος σε σχέση και απόσταση απο τη διακυβέρνηση .Η οικονομία σε καμία περίπτωση δεν είναι απλά " κατω" απο την διακυβέρνηση . Αντανακλά και σχηματοποιει ταξικές σχέσεις αλλα μονίμως είναι σε μια ένταση με την εξουσία .

Τον προβληματισμό αυτο αναπτύσσει ο G.Agamben στο τριτο μέρος του Homo Sacer " Il Regno e la Gloria" .Στο έργο αυτο ο GA προχωρά και εξελίσσει την θεματολογία της Πολιτικής Θεολογίας προς μια θεματολογία Οικονομικής Θεολογίας .Αν η Πολιτικη Θεολογια στηρίζεται στην θέση οτι οι σύγχρονες πολιτικές έννοιες προέρχονται απο της Θεολογία, η Οικονομική Θεολογία στηριζεται στην θεση ότι η σχέση εξουσίας οικονομίας έχει τη μορφή της τριαδικης υπόστασης του Θεού . Εκκεντρικό θεωρημα ίσως , αλλα για αυτο ο GA αφιερώνει διακόσιες πυκνες σελίδες .

Χοντρικά η εξέταση του GA είναι η ακόλουθη:

Όταν η χριστιανική Θεολογία αναπτύσσει την έννοια της τριαδικης υπόστασης, για να μην περιπέσει ουσιαστικά σε ένα τριθεισμό ,εισάγει εντος θεολογίας μια έννοια εκτός αυτής : την έννοια της αριστοτελικης οικονομίας .Με την εισαγωγή της έννοιας της οικονομίας οι τρεις υποστασεις του θείου συγκροτούνται σε μια δυναμική σχέση .Παράγωγες της τριαδικης υπόστασης είναι οι εννοιες της θειας πρόνοιας και η ανάγκη εισαγωγής της κατηγορίας, του συνόλου των αγγέλων .

Σύμφωνα με τον GA η αριστοτελικη οικονομία δεν είναι επιστήμη , αλλα πράξις. Δεν ορίζει ένα δομημένο τομέα έρευνας και ανάλυσης αλλα είναι διεκπεραίωση , διαδικασία ,πράξη.Η οικονομία είναι διαχείριση του οίκου σε αντιδιαστολή με την πολιτικη που είναι διαχείριση των της πόλης.Αυτη λοιπόν έννοια της οικονομίας εισάγεται στην Θεολογία για να σχηματοποιηθει το δυναμικό πλάσμα του τριαδικου θεού.

Το ενδιαφέρον που αποκαλύπτει ο GΑ ,μεσω μιας ενδελεχούς ιστορικής έρευνας ,είναι ότι αυτή η θεολογική οικονομία " επανεξαγεται " απο την Θεολογία προς την οικονομία των φυσιοκρατών δεκαπέντε αιώνες μετά. Το ιστορικό σχημα είναι περίπου το εξής:

Η Χριστιανικη Θεολογία έχει ανάγκη την έννοια της οικονομίας για να μην παλινδρομησει σε πολυθεϊσμό , την εισάγει στην τριαδικη υπόσταση, και αυτήν την θεολογική " οικονομία " διαχειρίζονται οι φυσιοκράτες για να να εξελιξουμε ως τις μέρες μας ως επιστήμη.Για να κατανοήσουμε λοιπον τις συγχρονες σχέσεις οικονομίας εξουσίας δεν έχουμε παρά να δούμε τις σχέσεις Θεού Υιού στο τριαδικό πλέγμα .

Η σημερινή οικονομία δεν είναι ουτε αυστηρή επιστήμη ούτε στεγνή πράξη , είναι μυστηριώδης όσο αναλογικά είναι μυστηριώδες το τριαδικό θεολογικο σχήμα το οποίο διαχωρίζει τον Θεό απο τις Πράξεις του.Ο GA προχωρεί ένα βήμα παραπάνω και διακρίνει στις μεγάλες διαμάχες του κατά του Μονοθεισμου μια κρίσιμη στροφή που επικυρωνει τον θεμελιακό δυϊσμό ,Θεού και Θείας Οικονομίας η οποία συγκροτεί και το μυστήριο της οικονομίας .Η άναρχη ισότιμη σχέση Θεού Υιου συγκροτεί ένα πεδίο πράξεων που δεν έχουν γραμμικη σχέση εκπορευσης απο το ένα του Θεού, αλλα αναδύονται εκ θεού ως μια ειδική θεία τυχαιοτητα . Αυτη την μυστηριώδη τυχαιοτητα αποκρυσταλλώνει η οικονομία .

Αν στο κλασικό σχήμα της πολιτικής θεολογίας του C Smitt η πολιτική εξουσία προέρχεται , καθρεφτίζεται, αναδύεται ως η μεταφορά του Θεού ,το κράτος έκτακτης ανάγκης ως το θαύμα κλπ κλπ στον G.Agamben η οικονομία αναβιώνει το δυναμικό σχήμα της τριαδικοτητας.Απο εκεί και πέρα αναπτύσσεται μια θεματολογία με εξαιρετική ευρηματικότητα και πρωτοτυπία .πχ όλη η σχετική Θεολογία των Αγγέλων ορίζεται απο τον GA ως η μήτρα μιας σχετικής σύγχρονης εξέτασης της γραφειοκρατία.Καλός ο Weber αλλά για να δούμε και τον Ακινάτη.....Στο ίδιο το βιβλίο του GA διαμορφώνεται με μια άλλη γιγάντια μεταφορά η οποία εξετάζει τις σχέσεις οικονομίας και οψης- θεάματος της εξουσίας , σε αντιστοιχία με τις σχέσεις τριαδικοτητας και δοξολογιας.Αυτο όμως είναι ένα άλλο εκκεντρικό θέμα ,άξιο ενός αλλού μικρού σχολιασμού.

Παρέκβαση : Ο Agamben και η αριστερά

Ο G.Agamben είναι προφανώς ένας απο τους πιο σημαντικούς σύγχρονους πολιτικούς φιλόσοφους με οξύ κριτικό προσανατολισμός.Ωστόσο όντας μαθητής του Heidegger δεν ανήκει τυπικά στο Χεγκελιανο Μαρξιστικο ρεύμα της Αριστεράς.Με μια έννοια η κριτική του είναι εξαιρετικά απαισιόδοξη, σχεδόν αποπνικτική . Το φράγμα αυτο , αυτήν την ορατή απόσταση , αποτυπώνει καθαρά ο διάλογος Negri Agamben όπως διεξάγεται τα τελευταία χρονιά .Είναι προφανώς αδύνατο αυτη η διαμάχη να αποτυπωθεί σε μια γραμμή ωστόσο χοντρικά μπορούμε να πούμε πως αν η " γυμνή ζωή " αποτελεί ένα όριο για τον GA με βάση την έννοια κλειδι του Homo Sacer ,στον ΑΝ η γυμνή ζωή δεν είναι όριο αλλα παραγωγή.Περισσότερα εδώ .Η σημείωση είναι απαραίτητη για να κατανοηθεί η πολιτικη Θεολογία του GA , και εισαγωγή του όρου της Οικονομικής Θεολογίας . Όπως και σε όλο το έργο του , η κριτική του είναι οξεία , διαβρωτική αλλά οι διέξοδοι που αναδύονται είτε είναι ελάχιστα ορατοί είτε σχεδόν εσχατολογικοί ( πχ Η κοινότητα που έρχεται )

Συνδέσεις:

Πυκνή παρουσιάση του ιδιου του Agamben για το "Il Regno e la Gloria " εδώ

G.Agamben : The Kingdom and the Glory (amazon)

Εικόνα : Dino Valls

Παρασκευή 2 Δεκεμβρίου 2011

R.Boer:ο Lenin και το οπιο.Περιπέτειες μιας μετάφρασης

In ‘Socialism and Religion’ from 1905, Lenin famously wrote:

Religion is opium of the people [опиум народа, opium naroda]. Religion is a sort of spiritual booze, in which the slaves of capital drown their human image [образ obraz], their demand for a life more or less worthy of man.

This text is of course a direct allusion to Marx’s even more famous observation:

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people [das Opium des Volkes] (Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law: Introduction. In Marx and Engels Collected Works, pp. 175-6).

An initial reading may attribute to Marx’s more elaborate prose a more subtle appreciation of religion – as both expression and protest, as the sigh, heart and soul of oppressed creatures in a heartless, soulless world. And a closer study of the key term, opium, reveals a profound multivalence in Marx’s usage. For opium was both a cheap curse of the poor and a vital medicine, a source of addiction and of inspiration for poets, writers and artists, the basis of colonial exploitation (in the British Empire) and of the economic conditions that allowed Marx and Engels to continue work relatively unmolested, in short, it ranged all the way from blessed medicine to recreational curse. As the left-leaning theologian, Metropolitan Vvedensky said already in Russia in 1925, opium is not merely a drug that dulls the senses, but also a medicine that ‘reduces pain in life and, from this point of view, opium is for us a treasure that keeps on giving, drop by drop’ (in debate with Anatoly Lunacharsky, 21-2 September, 1925). That Marx himself was a regular user of opium increases the complexity of the term in this text. Along with ‘medicines’ such as arsenic and creosote, Marx imbibed opium to deal with his carbuncles, liver problems, toothaches, eye pain, ear aches, bronchial coughs and so on – the multitude of ailments that came with chronic overwork, lack of sleep, chain smoking and endless pots of coffee.

Do we find this multivalence in Lenin’s recasting of the opium metaphor? Marx’s ‘opium of the people [das Opium des Volkes] is directly translated as ‘opium of the people’ [опиум народа, opium naroda]. The usage is the same, with a genitive in Russian. Unfortunately, the English translation in Lenin’s Collected Works renders the phrase in the dative, ‘opium for the people’, thereby producing the sense that religious beliefs are imposed upon people rather than emerging as their own response: religion is no longer of themselves, but has become something devised for them. Such a translation may have been preferred due to Lenin’s swift gloss, ‘a sort of spiritual booze’ [род ду ховной сивухи, rod duhovnoi sivuhi], which seems to reinforce this impression. And does not the next phrase – ‘in which the slaves of capital drown their human image’ – deploy the conventional role of alcohol, in which sorrows are drowned? Religion becomes a bottle of wine, a carton of beer, a flask of vodka, with which one dulls the pain of everyday life.

It is worth noting here that even if Lenin did use the genitive construction (following Marx), in the USSR the dative construction came to dominate. Thus, as Sergey Kozin points out, people mostly used the phrase ‘opium for the people’ rather than ‘opium of the people’ as the standard definition of religion. Perhaps the most famous example is the line from the movie, Twelve Chairs (based on Ilf and Petrov’s satirical novel of the same name from 1928) where the main character keeps greeting his competitor, the Orthodox priest, with the line: ‘How much do you charge for the opium for the people?’

In order to draw us back to the ambivalence embodied in the ‘opium of the people’, we need to consider carefully the rest of Lenin’s description. He introduces two items: ‘human image’ [человеческий образ] and ‘their demand for a life more or less worthy of human beings’ [свои требования на сколько-нибудь достойную человека жизнь]. Both terms – human image and decent human life – wrench the text away from a simple drowning of sorrows.

At first sight these terms seem like alternative ways of saying the same thing. Yet, the fact that they appear side by side introduces a minimal difference between them, one that is exacerbated by the biblical and theological echoes in Lenin’s text. Recall Genesis 1:26, where we find that the human beings are created in the ‘image of God’: ‘Let us make humankind in our image [tselem], according to our likeness’ [demuth]. Here too we find a minimal difference, between image and likeness; here too they seem to speak of the same thing, and yet they are different.

Lenin’s own context was infused with Orthodox theology and it is precisely that tradition which exploits the distinction between the two terms. Thus, while Adam and Eve may have been created in the image of God, being thereby able to participate in the divine life – when they were fully human – sin has blurred and fractured the union of divine and human, resulting in a situation that is less than human, with the unnatural result of death. However, in Orthodox theology after St. Maximus, what went ‘missing’ after enjoying the fruit of the tree was not so much the ‘image’, but the ‘likeness’. Christ’s central task in salvation is thereby not merely a process of restoring the pre-lapsarian state, but rather a new state achieved uniquely in Christ, which was not there with Adam and Eve. That is, beyond the image, one becomes a likeness of God – theosis, or deification. Indeed, theosis actually designates a closer fellowship with God than even the first human beings experienced. Christ may be the second Adam, but he is also more than that, enabling a far greater communion that was initially the case – so much that Christ may well have been incarnated simply for that reason, even without the first stumble.

Is it possible that Lenin, without necessarily evoking the whole economy of salvation, alludes to his complex interplay between image and likeness, with his usage of ‘human image’ and ‘worthy human life’? Our human image may be obscured, drowned, inebriated, blurred – as though one were blind drunk – but even so the demand for a decent life persists. That is, a life worthy of human beings echoes not merely the broken image that runs through Orthodoxy, but especially the restoration to the likeness of God through Christ.

At the same time, Lenin turns this theological heritage of the image and likeness on its head. Rather than staying within the theological framework and asking why it is that human beings are sinful, he accuses the framework itself with creating the problem in the first place. The issue is neither human culpability nor even the deception at the hands of third party, but rather religion itself. Let me put it this way: Lenin unwittingly parleys one tradition of interpretation against another, for the narrative of Genesis 1-3 opens up a third, rarely travelled path of interpretation, in which the one responsible for the Garden of Eden with its two trees – the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and the tree of life – is also thereby responsible for the act that sends the likeness into exile. If God had not created the flawed crystal of the Garden in the first place, the Fall would not have happened, despite its narrative necessity for the rest of the Bible (it would have been a drab story indeed if the first humans had remained in the state of paradisal bliss for page after page). It is a charge that the deity refuses to answer, so keen is he to lay the blame with the human beings and serpent, who are punished as he sees fit. By contrast, Lenin does lay the blame precisely here. Only when that has been addressed may a worthy human life – now a very human ‘likeness’ – be attained.

But what about that famous spiritual booze? Might that not also be a richer metaphor? To begin with, in 1925 the Moscow Metropolitan of the Orthodox Church, Alexander Vvedensky, pointed out that ‘booze’ is a good translation of ‘opium’, which opens Lenin’s phrase up to more ambiguity. But we also need to combine that fact with a greater appreciation of the role of alcohol in Russian culture. Even today, one finds that beer has only recently (2011) been designated an alcoholic drink, although most people continue to think that it is not. Even after this legislation, not much has changed in Russia’s beer-drinking culture except that Medvedev’s ‘police’ increasingly fine youngsters for drinking in public. Two-liter bottles are still available in most shops. And the famed vodka may be bought in bottles that fit comfortably in one’s hand, a necessary feature due to that great Russian tradition in which an opened bottle must be emptied. Italy and France may be fabled as wine cultures, Germany, Scandinavia and Australia as beer cultures, but Russia’s drinking identity is inseparable from vodka. Russians may be admired for their fabled drinking prowess, vodka may be a necessary complement to any long-distance rail travel (as I have found more than once), it may be offered to guests at the moment of arrival (for otherwise the host is unforgivably rude), it may be an inseparable element of the celebration of life, but it is also the focus of age-long concern. One may trace continued efforts to curtail excessive consumption all the way back to Lenin. For example, Krushchev and Breshnev sought in turn to restrict access to vodka with tighter controls, although their efforts pale by comparison to the massive campaign launched by Gorbachev in 1985. And Lenin fumed at troops and grain handlers getting drunk, molesting peasants and stealing grain during the dreadful famines (or rather, during the period of a lack of means to transport grain to areas where it was desperately needed) during the foreign intervention after the Revolution. Nonetheless, vodka was a vital economic product. Already in 1899 in his painstakingly detailed The Development of Capitalism in Russia, Lenin provides graphs and data concerning the rapid growth of distilling industry.

In other words, alcohol is as complex a metaphor as opium, if not more so. It is both spiritual booze and divine vodka: relief for the weary, succour to the oppressed, inescapable social mediator, it is also a source of addiction, dulling of the senses and dissipater of strength and resolve. Religion-as-grog thereby opens up a far greater complexity concerning religion in Lenin’s thought than one may at first

Απο το ιστολόγιο Political Theology

Religion is opium of the people [опиум народа, opium naroda]. Religion is a sort of spiritual booze, in which the slaves of capital drown their human image [образ obraz], their demand for a life more or less worthy of man.

This text is of course a direct allusion to Marx’s even more famous observation:

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people [das Opium des Volkes] (Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law: Introduction. In Marx and Engels Collected Works, pp. 175-6).

An initial reading may attribute to Marx’s more elaborate prose a more subtle appreciation of religion – as both expression and protest, as the sigh, heart and soul of oppressed creatures in a heartless, soulless world. And a closer study of the key term, opium, reveals a profound multivalence in Marx’s usage. For opium was both a cheap curse of the poor and a vital medicine, a source of addiction and of inspiration for poets, writers and artists, the basis of colonial exploitation (in the British Empire) and of the economic conditions that allowed Marx and Engels to continue work relatively unmolested, in short, it ranged all the way from blessed medicine to recreational curse. As the left-leaning theologian, Metropolitan Vvedensky said already in Russia in 1925, opium is not merely a drug that dulls the senses, but also a medicine that ‘reduces pain in life and, from this point of view, opium is for us a treasure that keeps on giving, drop by drop’ (in debate with Anatoly Lunacharsky, 21-2 September, 1925). That Marx himself was a regular user of opium increases the complexity of the term in this text. Along with ‘medicines’ such as arsenic and creosote, Marx imbibed opium to deal with his carbuncles, liver problems, toothaches, eye pain, ear aches, bronchial coughs and so on – the multitude of ailments that came with chronic overwork, lack of sleep, chain smoking and endless pots of coffee.

Do we find this multivalence in Lenin’s recasting of the opium metaphor? Marx’s ‘opium of the people [das Opium des Volkes] is directly translated as ‘opium of the people’ [опиум народа, opium naroda]. The usage is the same, with a genitive in Russian. Unfortunately, the English translation in Lenin’s Collected Works renders the phrase in the dative, ‘opium for the people’, thereby producing the sense that religious beliefs are imposed upon people rather than emerging as their own response: religion is no longer of themselves, but has become something devised for them. Such a translation may have been preferred due to Lenin’s swift gloss, ‘a sort of spiritual booze’ [род ду ховной сивухи, rod duhovnoi sivuhi], which seems to reinforce this impression. And does not the next phrase – ‘in which the slaves of capital drown their human image’ – deploy the conventional role of alcohol, in which sorrows are drowned? Religion becomes a bottle of wine, a carton of beer, a flask of vodka, with which one dulls the pain of everyday life.

It is worth noting here that even if Lenin did use the genitive construction (following Marx), in the USSR the dative construction came to dominate. Thus, as Sergey Kozin points out, people mostly used the phrase ‘opium for the people’ rather than ‘opium of the people’ as the standard definition of religion. Perhaps the most famous example is the line from the movie, Twelve Chairs (based on Ilf and Petrov’s satirical novel of the same name from 1928) where the main character keeps greeting his competitor, the Orthodox priest, with the line: ‘How much do you charge for the opium for the people?’

In order to draw us back to the ambivalence embodied in the ‘opium of the people’, we need to consider carefully the rest of Lenin’s description. He introduces two items: ‘human image’ [человеческий образ] and ‘their demand for a life more or less worthy of human beings’ [свои требования на сколько-нибудь достойную человека жизнь]. Both terms – human image and decent human life – wrench the text away from a simple drowning of sorrows.

At first sight these terms seem like alternative ways of saying the same thing. Yet, the fact that they appear side by side introduces a minimal difference between them, one that is exacerbated by the biblical and theological echoes in Lenin’s text. Recall Genesis 1:26, where we find that the human beings are created in the ‘image of God’: ‘Let us make humankind in our image [tselem], according to our likeness’ [demuth]. Here too we find a minimal difference, between image and likeness; here too they seem to speak of the same thing, and yet they are different.

Lenin’s own context was infused with Orthodox theology and it is precisely that tradition which exploits the distinction between the two terms. Thus, while Adam and Eve may have been created in the image of God, being thereby able to participate in the divine life – when they were fully human – sin has blurred and fractured the union of divine and human, resulting in a situation that is less than human, with the unnatural result of death. However, in Orthodox theology after St. Maximus, what went ‘missing’ after enjoying the fruit of the tree was not so much the ‘image’, but the ‘likeness’. Christ’s central task in salvation is thereby not merely a process of restoring the pre-lapsarian state, but rather a new state achieved uniquely in Christ, which was not there with Adam and Eve. That is, beyond the image, one becomes a likeness of God – theosis, or deification. Indeed, theosis actually designates a closer fellowship with God than even the first human beings experienced. Christ may be the second Adam, but he is also more than that, enabling a far greater communion that was initially the case – so much that Christ may well have been incarnated simply for that reason, even without the first stumble.

Is it possible that Lenin, without necessarily evoking the whole economy of salvation, alludes to his complex interplay between image and likeness, with his usage of ‘human image’ and ‘worthy human life’? Our human image may be obscured, drowned, inebriated, blurred – as though one were blind drunk – but even so the demand for a decent life persists. That is, a life worthy of human beings echoes not merely the broken image that runs through Orthodoxy, but especially the restoration to the likeness of God through Christ.

At the same time, Lenin turns this theological heritage of the image and likeness on its head. Rather than staying within the theological framework and asking why it is that human beings are sinful, he accuses the framework itself with creating the problem in the first place. The issue is neither human culpability nor even the deception at the hands of third party, but rather religion itself. Let me put it this way: Lenin unwittingly parleys one tradition of interpretation against another, for the narrative of Genesis 1-3 opens up a third, rarely travelled path of interpretation, in which the one responsible for the Garden of Eden with its two trees – the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and the tree of life – is also thereby responsible for the act that sends the likeness into exile. If God had not created the flawed crystal of the Garden in the first place, the Fall would not have happened, despite its narrative necessity for the rest of the Bible (it would have been a drab story indeed if the first humans had remained in the state of paradisal bliss for page after page). It is a charge that the deity refuses to answer, so keen is he to lay the blame with the human beings and serpent, who are punished as he sees fit. By contrast, Lenin does lay the blame precisely here. Only when that has been addressed may a worthy human life – now a very human ‘likeness’ – be attained.

But what about that famous spiritual booze? Might that not also be a richer metaphor? To begin with, in 1925 the Moscow Metropolitan of the Orthodox Church, Alexander Vvedensky, pointed out that ‘booze’ is a good translation of ‘opium’, which opens Lenin’s phrase up to more ambiguity. But we also need to combine that fact with a greater appreciation of the role of alcohol in Russian culture. Even today, one finds that beer has only recently (2011) been designated an alcoholic drink, although most people continue to think that it is not. Even after this legislation, not much has changed in Russia’s beer-drinking culture except that Medvedev’s ‘police’ increasingly fine youngsters for drinking in public. Two-liter bottles are still available in most shops. And the famed vodka may be bought in bottles that fit comfortably in one’s hand, a necessary feature due to that great Russian tradition in which an opened bottle must be emptied. Italy and France may be fabled as wine cultures, Germany, Scandinavia and Australia as beer cultures, but Russia’s drinking identity is inseparable from vodka. Russians may be admired for their fabled drinking prowess, vodka may be a necessary complement to any long-distance rail travel (as I have found more than once), it may be offered to guests at the moment of arrival (for otherwise the host is unforgivably rude), it may be an inseparable element of the celebration of life, but it is also the focus of age-long concern. One may trace continued efforts to curtail excessive consumption all the way back to Lenin. For example, Krushchev and Breshnev sought in turn to restrict access to vodka with tighter controls, although their efforts pale by comparison to the massive campaign launched by Gorbachev in 1985. And Lenin fumed at troops and grain handlers getting drunk, molesting peasants and stealing grain during the dreadful famines (or rather, during the period of a lack of means to transport grain to areas where it was desperately needed) during the foreign intervention after the Revolution. Nonetheless, vodka was a vital economic product. Already in 1899 in his painstakingly detailed The Development of Capitalism in Russia, Lenin provides graphs and data concerning the rapid growth of distilling industry.

In other words, alcohol is as complex a metaphor as opium, if not more so. It is both spiritual booze and divine vodka: relief for the weary, succour to the oppressed, inescapable social mediator, it is also a source of addiction, dulling of the senses and dissipater of strength and resolve. Religion-as-grog thereby opens up a far greater complexity concerning religion in Lenin’s thought than one may at first

Απο το ιστολόγιο Political Theology

Δευτέρα 28 Νοεμβρίου 2011

Τι δεν είναι και τι είναι μια Αριστερή Πολιτική Θεολογία

Δεν είναι λόγος περί του ιερού, του θείου, του θεού.

Δεν είναι η πολιτική διαπραγμάτευση των πολιτικών κινημάτων με θρησκευτική προέλευση

Δεν είναι η πολιτική διαπραγμάτευση των κοσμικών και πολιτικών εκφράσεων των επίσημων ή κρατουσών θρησκειών

Δεν είναι κοινωνιολογία των θρησκειών

Είναι η ανάλυση, αναδιαπραγμάτευση, ζητημάτων της αριστεράς με την χρήση εννοιών, συμφραζομένων, παραδειγμάτων , αναλύσεων που προέρχονται από την θεολογία.

Πηγή της αριστερής πολιτικής θεολογίας είναι η θέση πως όλες οι έννοιες της σύγχρονης πολιτικής προέρχονται από την θεολογία (Carl Schmitt)

Πηγή της αριστερής πολιτικής θεολογίας είναι η εκτεταμένη και ζωσα λειτουργία βιβλικών και θεολογικών αναφορών στο έργο των Benjamin,Altusser,Negri,Badiou,Zizek,Bloch, Adorno κλπ

Εικόνα : Dino Vals

Κυριακή 27 Νοεμβρίου 2011

Giorgio Agamben on Economic Theology

The Power and the Glory: Giorgio Agamben on Economic Theology

This is a transcript of a talk given by Agamben in Turino on January 11, 2007, continuing the studies of Michel Foucault on the genealogy of governance.

By Giorgio Agamben

"The Power and the Glory", Giorgio Agamben, 11th B.N. Ganguli Memorial Lecture, CSDS, 11th January 2007.

Editor's Note: I have not adjusted the obvious misspellings and errors in this transcription.

This investigation concerns the reasons and modalities through which power has taken in western societies the form of an economy. That is to say, of a government of man and things. So we must speak about power in general as about a peculiar form of power, the modern form of power, that is to say, government. Of course I will therefore have to carry on Michel Foucault's enquiries in the genealogy of governance.